In Rabelais and His World, Mikhail Bakhtin emphasizes the importance of laughter in the popular-festive tradition. He asserts that narrow-minded seriousness cannot coexist with Rabelaisian images, which “are opposed to all that is finished and polished, to all pomposity, to every ready-made solution in the sphere of thought and world outlook” (3). It follows that film comedy, of all cinematic genres, is the one that most obviously lends itself to Bakhtin’s notion of the carnivalesque.

However, the subversion and grotesquerie that Bakhtin identifies in Rabelais is equally present in the experimental works of the avant-garde, albeit at the expense of accessibility to the masses. Robert Stam writes:

In the modernist period, the carnivalesque ceases to be a collective cleansing ritual open to all “the people” to become the monopoly of a marginalized caste. Carnival, in this modified and somewhat hostile form, is present in the outrageousness of Dada, the provocations of surrealism, in the travesty-revolts of Genet’s The Maids or The Blacks, and indeed in the avant-garde generally. (169)

This “somewhat hostile form” often takes shape within cinema as works that subvert the conventions of traditional film continuity. In Isidore Isou’s 1951 film Traité de bave et d’éternité (or Venom and Eternity), the dominant carnivalesque strategy is not laughter, but negation, specifically the negation of the image.

Isou was the founder of Lettrism, a French avant-garde movement devoted to creativity and originality above all else. Begun as a one-man movement, Lettrism gained a following of disciples, indeed qualifying it as a “marginalized caste.” Isou identified two kinds of phases in the history of poetry: the “amplique” phase, characterized by innovation and growth; and, following the exhaustion of creative possibilities, the deconstructive “ciselante” (or “chiseling”) phase. The latter reduced poetry to its simplest elements, from poetic form to verse to word to sound pattern to nonsense, and finally with Lettrism, to the letter (Kaufmann 83).

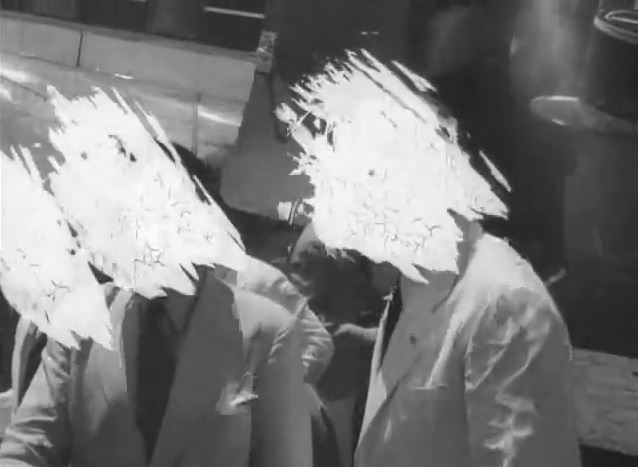

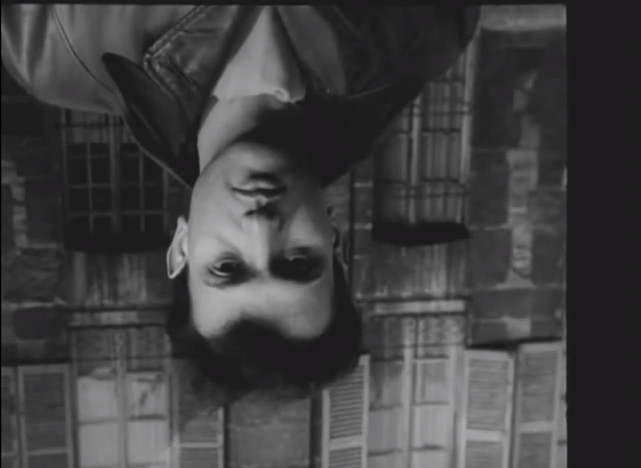

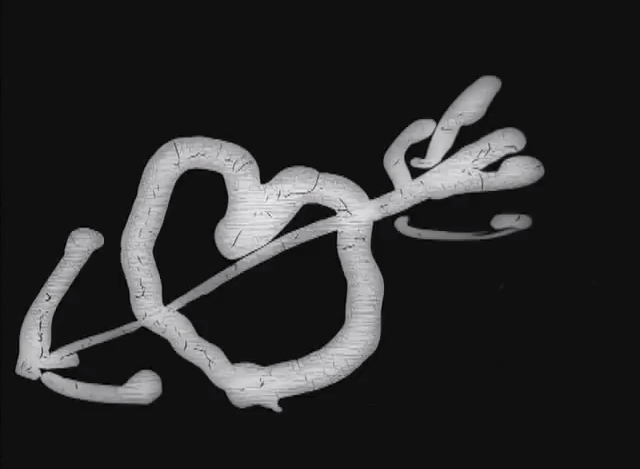

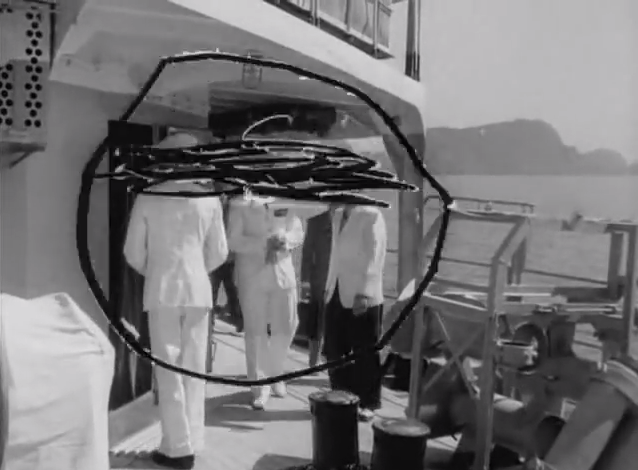

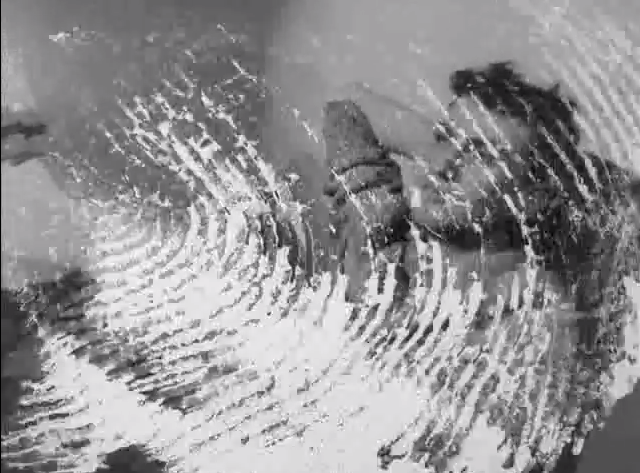

By 1950, Isou felt that cinema had exhausted its own creative possibilities, and he set out to initiate a chiseling phase, a “willful accumulation of errors” that he labeled “discrepant cinema.” By showing only footage that is not related to the soundtrack narration, and by debasing the image in various ways–painting directly onto the film stock, bleaching out people’s heads, scratching the film emulsion, flipping images upside down and playing them in reverse–Isou breaks the connection between image and language, the latter of which he considers more important to the evolution of cinema.

Although the title of Isou’s film is commonly translated into English as Venom and Eternity, a more literal translation is Treatise on Slime and Eternity, which accurately describes the film: it is a treatise arguing for a new form of cinema, but it is also a fictional narrative assembled in the proposed cinematic form. It deals with destruction as a necessary step toward reinvention; the “venom” or “slime” of the title connotes the negative (slime being a low, disgusting thing) as well as the positive (in the sense that life emerged from the “primordial slime”).

The film (henceforth Venom and Eternity) is divided into three chapters–“The Principle”, “The Development”, and “The Proof.” “The Principle” is a manifesto delivered by Isou in the guise of an ostensibly fictional character named Daniel. Daniel differs from Isou in name only: like Isou, Daniel is the founder of Lettrism, and he seeks to make the film that Isou has already made with Venom and Eternity. Though Isou eschews direct address in his narration, opting to present himself only as a fictional character, he appears onscreen throughout the first chapter, swaggering around the streets of St. Germain des Prés and staring directly into the camera. As will be seen in further examples, the image of Isou as Daniel is self-reflexive while the narration is not.

Daniel is heard delivering his manifesto inside a film club, where an audience jeers at him and shouts epithets. The essence of Daniel’s speech is the Rabelaisian concept that cinema must be destroyed in order to be created anew: “In Rabelais’ novel [Gargantua] the image of death is devoid of all tragic or terrifying overtones. Death is the necessary link in the process of the people’s growth and renewal. It is the ‘other side’ of birth” (Bakhtin 407). The destruction of the old and birth of the new world is precisely the object of celebration in Carnival–hence negation as a carnivalesque strategy, and the one favored by Isou.

The negation of the image does not translate to the nonexistence of the image. Though Isou wants cinema to be rooted in language, at one point asking why cinema shouldn’t become a species of radio, he rarely deprives the audience of any image whatsoever. Instead, in a manner reminiscent of Alfred Jarry, he uses discontinuity to provoke and offend the public, or in Isou’s case, to offend cinephiles who are optimistic about the future of film (Stam 8). In so doing, he turns cinema on its head, not just figuratively but literally as well, when he flips the image upside down. Bakhtin writes:

That which stands behind negation is by no means nothingness but the ‘other side’ of that which is denied, the carnivalesque upside down. Negation reconstructs the image of the object and first of all modifies the topographical position in space of the object as a whole, as well as of its parts. It transfers the object to the underworld, replaces the top by the bottom, or the front by the back, sharply exaggerating some traits at the expense of others. Negation and destruction of the object are therefore their displacement and reconstruction in space. The nonbeing of an object is its ‘other face,’ its inside out. And this inside out or lower stratum acquires a time element; it may be conceived as the past, the obsolete, or the nonexistent. The object that has been destroyed remains in the world but in a new form of being in time and space; it becomes the ‘other side’ of the new object that has taken place.” (410)

Isou’s literal modification of topographical position, a cinematic rendering of a world upside down, is characteristic of a downward movement that is found in both popular-festive merriment as well as grotesque realism, manifested in Rabelais as a movement toward both an earthly and bodily underworld: “Down, inside out, vice versa, upside down, such is the direction of all these movements. All of them thrust down, turn over, push headfirst, transfer top to bottom, and bottom to top, both in the literal sense of space, and in the metaphorical meaning of the image” (Bakhtin 370). Later in Venom and Eternity, Daniel predicts that his film shall be “like hell composed of circles,” circles comprising the things he holds dearest. A descent into the lower depths is thus ennobled, and the “completed, perfect quality” of existing films is denounced in a carnivalesque subversion of the traditional hierarchy of film practice.

Throughout his speech to the film club, Daniel makes a series of hyperbolic and exaggerated statements: “I like the Cinema when it is insolent and behaves as it shouldn’t”; “Everything that has existed is bad”; “One must go beyond the image and attack the film stock”; “I want to make a film that hurts your eyes”; “I would rather give you a migraine than nothing at all.” He concludes that those to whom he is addressing his manifesto are “a bunch of idiots.” One of those in attendance, a character named “The Stranger,” later defends Daniel with additional hyperbole:

By destroying the image, Daniel splits the image, makes it more intelligent than an ordinary image, because a destructive image is superior to an ordinary image. Else it could not destroy it. One must be stronger and superior to someone to beat him. Therefore, your film will be the most interesting in the history of cinema.

At one point in the film, Daniel states: “I know that my film is above all existing films today. I myself am above my own film.” Such conceit seems absurdly exaggerated, and is not likely tongue-in-cheek considering Isou’s reputation for megalomania (Kaufmann 81). In Bakhtin’s terms, however, the aforementioned statements are compatible with the grotesque style of the carnivalesque tradition, of which he considers exaggeration, hyperbolism, and excessiveness to be fundamental attributes (303).

Isou ends the first chapter with a title that reads, “I hope you’ll find the second part more fun.” This seemingly self-deprecating remark presupposes that the audience has not been enjoying the film up to this point. It also addresses the audience directly from the perspective of the author; this occurs frequently in the titles that appear throughout the film, but as mentioned before, it is only when there is no spoken narration in conjunction with the onscreen text: the soundtrack is limited to the world of the diegesis. The key characteristic that makes the second chapter “more fun”–that is to say, more accessible from a narrative standpoint, in spite of the continued discrepancy of the image–is the love story it introduces. The banality of this love story becomes the subject of self-reflexive commentary, but without ever disrupting the spoken narrative.

According to the credits preceding “The Development”, the character of Eve is portrayed by Colette Garrigue. When Eve is introduced in the narrative, a woman is shown onscreen, but a credit title identifies her as Blanchette Brunoy, not Colette Garrigue. This self-reflexive visual tactic foregrounds the discrepancy between sound and image, specifically between the dual portrayals of Eve. The narrator states that Eve’s bearing is “that of a wicked empress, a marble as cold as a sculptural image of War,” but Brunoy appears cheerful and radiant. As the narrator proceeds to chronicle Daniel and Eve’s relationship at length, footage is shown of Isou and Brunoy walking arm in arm, as if to supplement the banal subject matter formulating the narrative. However, these images are joined in the chapter by far less congruous footage—manipulated images of men on a boat, a dog, people skiing–which reinforces the film’s aesthetic of sound-image discrepancy.

In the midst of his romance with Eve, Daniel recalls a previous girlfriend, Denise, with whom he had shared a sadomasochistic relationship:

He left his teethmarks upon her, and she bore black and blue marks, like his rubber stamp of jealous ownership. He despoiled her…he used her money. “Does she love me beyond her needs, beyond her daily bread?” And he broke her, he tore her to feel himself within her. He ravaged her to make himself unforgettable. He installed himself within her.

Aside from distancing the film’s protagonist from audiences who would traditionally align themselves to his desires, Daniel’s cataloguing of abusive behavior betrays his own need for acceptance: “Does she love me beyond her needs, beyond her daily bread?” There is ambivalence in the imagery of abuse that echoes Bakhtin, who relates the connection between abuse and praise in the language of the Rabelaisian marketplace to the carnivalesque connection between death and rebirth:

The popular-festive language of the marketplace abuses while praising and praises while abusing. It is a two-faced Janus. It is addressed to the dual-bodied object, to the dual-bodied world (for this language is always universal); it is directed at once to the dying and to what is being generated, to the past that gives birth to the future. Either praise or abuse may prevail, but the one is always on the brink of passing into the other. Praise implicitly contains abuse, is pregnant with abuse, and vice versa abuse is pregnant with praise. . . . Praise and abuse may be aligned or divided among private voices, but in the whole they are fused into ambivalent unity. (415-416)

In Venom and Eternity, there is ambivalent unity in the self-deprecating remarks that contradict Isou’s self-aggrandizement; in the appeal to destroy cinema in order for it to evolve; and in the decision to introduce a new form of cinema via something as familiar as a love story.

A moment late in the film sheds some light on Isou’s motivation for centering his narrative on Daniel’s romantic escapades, when the character named “The Stranger” tells Daniel the following: “You will show images to draw attention to words. You could even tell a love story to remind one, in the shelter of that story, of another love, a rarer, more precious love.” The second chapter ends with scrolling credits offering a more cynical and more likely explanation:

The author of this picture, Jean-Isidore Isou, wrote this chapter during a spell of poisonous tenderness resembling that of the girls who emerge from his room with an ‘I love you’ meant for no one, and bursting with desire like a fruit into which no one will ever bite, so monstrous does it seem at a distance. But upon reading these lines over, on a day of love super-saturation, he found this entire chapter insipid. However, the author knows that people go to the movies to swallow their weekly Saturday night dose of tenderness. And though they don’t give a hoot about the story, they retell it in the hope of a deserved success. The author does not care for this type of legend, because these are questions of personal taste. Only systems where form goes beyond story are of interest to him.

Again, Isou identifies himself as the author, not within the voiceover narrative but through intertitles. He no longer merely expresses hope that the viewer will find the material that follows “more fun” than what preceded it; now, he outright dismisses the second chapter as “insipid,” as if to vindicate himself by self-reflexively distancing his narrative from precisely the category of stories to which it belongs. Thus, abuse and praise are fused into ambivalent unity.

“The Proof” begins with Daniel and Eve attending a Lettrist poetry recital. The theory of Lettrism developed by Isou prior to making Venom and Eternity called for the negation of articulate language, and it “challenged the false appearance of communication demanded by the power structure” (Kaufmann 176). Just as Venom and Eternity negates the image, not by eliminating its existence entirely but by defacing it, so does Lettrist poetry negate language, not with silence, but with an absolute and external form of noncommunication, expressed as gibberish. One may find similarity in Bakhtin’s description of a popular form of comic speech during the Middle Ages, the “coq-a-l’ane” (“from rooster to ass”):

This is a genre of intentionally absurd verbal combinations, a form of completely liberated speech that ignores all norms, even those of elementary logic. . . . It is as if words had been released from the shackles of sense, to enjoy a play period of complete freedom and establish unusual relationships among themselves. (Bakhtin 422-3)

Like the coq-a-l’ane, Lettrist poetry is a form of carnivalesque language. Its challenge to “the false appearance of communication demanded by the power structure” is a challenge to the hierarchy of social practices and norms, as Robert Stam explains: “The linguistic corollary of carnivalization entails the liberation of language from the norms of decency and etiquette. Carnivalesque language is designed to degrade all that is spiritual and abstract; it transfers the ideal to a brute material level” (169). In Lettrist poetry, the other side of the abuse of language is the praise of the letter. Isou states that the poems “were composed solely for the beauty of pure noise, for the harmony of outcry.” However, in reverence to narrative conventions, the poems recited in Venom and Eternity are presented as part of the film’s fictional scenario.

The viewer is told that Daniel and Eve “let themselves drift into the orbit of Lettrist folly.” For a film in which Lettrism and its founder are lavished with bombastic praise, it bears notice that Lettrist poetry is described here as “folly.” In fact, the word carries greater ambivalence than its negative connotation may suggest, as Bakhtin explains:

It has the negative element of debasement and destruction (the only vestige now is the use of ‘fool’ as a pejorative) and the positive element of renewal and truth. Folly is the opposite of wisdom–inverted wisdom, inverted truth. It is the other side, the lower stratum of official laws and conventions, derived from them. (Bakhtin 260)

Isou evokes the notion of inverted wisdom when he states in the narration that Daniel would be “an exotic fool to all imbeciles.” As Bakhtin writes of the clown: “he is king of a world ‘turned inside out’” (370).

Daniel is prepared to counter criticism of his willfully accumulated errors with the argument that there are no perfect works. For Isou, cinema is in a perpetual state of incompletion. Referencing two figures of the Enlightenment, Eve tells Daniel:

All images are equally indifferent. Madame de Charriere told Benjamin Constant that God existed but died during the creation of this unfinished world, that the universe you see is but the scaffolding of a never-to-be-completed universe. Similarly, the Cinema shall never again be what it used to be. If I follow you correctly, Daniel, according to you the God of the Cinema is dead.

Cinema, then, is an embodiment of the grotesque realism that informs the carnivalesque. Bakhtin writes: “The grotesque body, as we have often stressed, is a body in the act of becoming. It is never finished, never completed; it is continually built, created, and builds and creates another body” (317). This other body, the one of Isou’s film, is incomplete in yet another fashion, as the viewer eventually learns from the author’s intertitles: his film was originally four and a half hours long.

The remainder of Venom and Eternity finds Daniel growing tired of Eve and rejecting her, after which she goes insane and is deported. A sense of circularity arises from the fact that Daniel will proceed to make Venom and Eternity, the film that Isou has already made, and which has now reached its end. In spite of such inferred self-awareness and the subversion of the traditional “happy ending,” the spoken narration never demonstrates explicit self-reflexivity, instead remaining as linear and free of disruption as the traditional Hollywood-style narrative. Isou only inserts himself indirectly by having fictional characters express his proclamations for him. Visually, however, the film is rarely anything but self-reflexive, given the centrality of destroyed images to Isou’s aesthetic. It is as if there are two narrational modes, the aural and the visual, and only in the latter may the viewer find examples of carnivalesque self-reflexivity. In its totality, Isou’s film engages in authorial intrusion, most obviously when he incorporates himself into intertitles; however, the discrepancy between sound and image allows the fictional scenario to proceed on its own course without any such intrusion.

Venom and Eternity is a treatise within a fictional narrative, in the sense that Isou’s fictional counterpart, Daniel, serves as the mouthpiece for Isou’s theory of “discrepant cinema.” However, it is also a fictional narrative within a treatise, since Daniel’s story is surrounded by a self-reflexive framework of authorial address, manifested in intertitles. These intertitles are not read by Isou, and therefore never intrude on the diegetic sound world; instead they reside within the discrepant visual realm of “chiseled photography.” Consider the following, which appears early in the film as intertitles directly from the author:

In an era where everyone is concerned with beautiful photography, the point here is to destroy the image. By destroying the object of painting, Picasso gave a new purpose to painting. That is why the painters of colored picture post-cards are failures. On the other hand, we have been able, for the first time in the annals of the Cinema, to complete a scenario independent in itself, without being forced to intercut it with “visual elements.” Therefore, an attentive spectator will be able to hear the most beautiful scenario in the history of the Cinema.

Even disregarding the hyperbole of the last sentence, it is questionable whether Isou truly achieves what he claims to have achieved. While his scenario is independent in itself, being limited only to soundtrack narration, he makes his assertion regarding “visual elements” through the visual element of onscreen text. Less questionable, however, is the place that Venom and Eternity holds, within both avant-garde cinema as well as the Bakhtinian tradition of the carnivalesque. The latter, often linked to comic genres, bears equal relevance to the subversions of the avant-garde.

REFERENCES

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. 1968. Bloomington, IN: Indiana UP, 1984.

Kaufmann, Vincent. Guy Debord: Revolution in the Service of Poetry. Trans. Robert Bononno. Minneapolis: Minnesota UP.

Stam, Robert. Reflexivity in Film and Literature. 1985. New York: Columbia UP, 1992.

Traité de bave et d’éternité. Dir. Isidore Isou. 1951. DVD. Avant-Garde 2: Experimental Cinema 1928-1954. Kino International Corporation, 2007.